The Name Dan in Japanese/Chinese on a Custom-Made Wall Scroll.

Click the "Customize" button next to your name below to start your personalized dan calligraphy artwork...

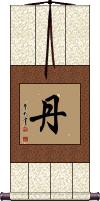

1. Dan

2. Go-Dan / 5th Degree Black Belt

4. Ku-Dan

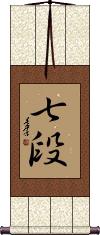

5. Nana-Dan / 7th Degree Black Belt

6. Ni-Dan

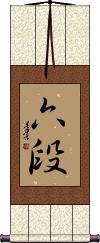

7. Roku-Dan / 6th Degree Black Belt

8. San-Dan

9. Sho-Dan

10. Yon-Dan

Go-Dan / 5th Degree Black Belt

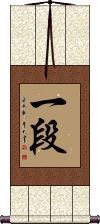

Ichi-Dan / First Degree

In Japanese martial arts, this usually represents the first-degree black belt rank.

It can also be like a linguistic stair step of “more, much more, still more, all the more.” It can also be a step, rung, level, or rank.

Also sometimes used in the context of Buddhism to mean “first step” or “first stage.” This might presume the first step towards enlightenment etc.

Ku-Dan

Nana-Dan / 7th Degree Black Belt

Ni-Dan

二段 is a Japanese Kanji word that literally means “second degree.”

二段 is the second black belt rank in Japanese martial arts.

The first Kanji means two or second in Japanese.

The second Kanji means step, grade, rank, or level.

二段 can also be written as 弐段. This version just uses a more complicated Kanji for the number two.

Roku-Dan / 6th Degree Black Belt

六段 is the Japanese title for the 6th Degree or 6th Level.

This applies mostly to martial arts and earning the title of a 6th-degree black belt.

The first character is simply the number 6.

The second character is “dan” which is often translated as “degree” in the context of Japanese martial arts. 六段 means grade, rank, level. When a number is in front like this, it refers to a senior rank in martial arts or games of strategy such as go, shogi, chess, etc.

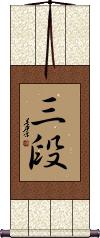

San-Dan

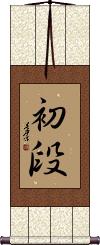

Sho-Dan

Yon-Dan

The following table may be helpful for those studying Chinese or Japanese...

| Title | Characters | Romaji (Romanized Japanese) | Various forms of Romanized Chinese | |

| Dan | 丹 | dān / dan1 / dan | tan | |

| Dan | ダン | dan | ||

| Go-Dan 5th Degree Black Belt | 五段 | go dan / godan | ||

| Ichi-Dan First Degree | 一段 | ichi dan / ichidan | yī duàn / yi1 duan4 / yi duan / yiduan | i tuan / ituan |

| Ku-Dan | 九段 | ku dan / kudan | ||

| Nana-Dan 7th Degree Black Belt | 七段 | nana dan / nanadan | ||

| Ni-Dan | 二段 | ni dan / nidan | ||

| Roku-Dan 6th Degree Black Belt | 六段 | roku dan / rokudan | ||

| San-Dan | 三段 | san dan / sandan | ||

| Sho-Dan | 初段 | sho dan / shodan | ||

| Yon-Dan | 四段 | yon dan / yondan | ||

| In some entries above you will see that characters have different versions above and below a line. In these cases, the characters above the line are Traditional Chinese, while the ones below are Simplified Chinese. | ||||